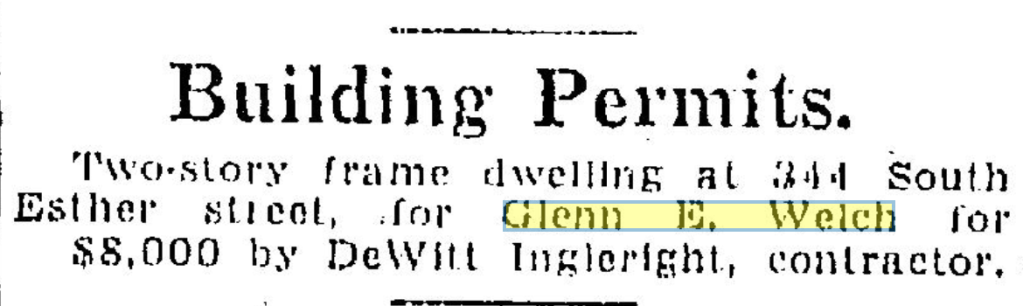

After a very frustrating week, which I will describe tomorrow when we expect to get answers, the weekend has been a relief being our little family with no workers around. It also gave me time to research some of the gaps in our understanding of the history of the house. For example, early in the 20th Century, the South Bend Tribune consistently listed building permits, but I couldn’t find any records for our house. In addition, our record of deeds implies that the original address for the property was on Madison Street. (We live on the corner of Esther and Madison Streets and it is clear that Glenn and Agda Welch bought two lots because they later built a house for their daughter and son in law on the second lot, facing Madison.) Then I remembered from my newspaper days how often reporters (and editors) misspelled names and addresses and that styles change in how papers referred to people. Because I was injured, I searched newspaper archives with various options. BINGO:

This is a surprisingly helpful find! Most importantly, it shows something that we were unsure about: Glenn and Agda were the designers–or design deciders, as we are now–of the house and what it included and did not. It also shows that the contractor, DeWitt Ingleright, was an unusual choice for Coquillard Woods as far as I can tell. Most of the homes that he built were in the Harter Heights neighborhood of South Bend, which is just south of Notre Dame and is where Amy Coney Barrett lived before she moved to be on the U.S. Supreme Court. Harter Heights was a very, very popular neighborhood for building in the early 1920s. (Of course, it was also the site of a number of foreclosures and Sheriff’s sales in the early 1930s.)

You can also see that the two-story home permit was valued at $8,000. That’s about $175,000 in today’s dollars. That’s a pretty penny but not extreme in 1936 in South Bend; let’s say upper middle class.

This also enlightens us about the design of the house. Remember that Glenn and Agda were 53 years old when they built the house. Their design choices that we can see have a little bit of modern (for 1936) features as well as quite traditional as one might expect for people who were relatively (and newly) wealthy and pretty elderly for the time; life expectancy in the U.S. was between 56 and 61. They actually died in their mid 70s and early 80s.

Yet their style sense might have had their roots in earlier times. They also were building the home for their own use, without children because their daughter was married and living with her husband in Glenn and Agda’s former home. All of this sheds some light–albeit total speculation based on hints we have–how they may have used the rooms.

First, at least one of them LOVED floral wallpaper.

These floral wallpapers were popular–and inexpensive–in the early 20th Century, according to ThisOldHouse.com. They don’t necessarily define a style for the home. The exterior style is hard to define, but the interior strongly echoes a Craftsman vibe with major features of wood trim–but not with the lines one would expect with anything Craftsman style home. The juxtaposition of the romantic wallpaper and the Craftsman-esque woodwork suggests that Glenn and Agda were building their own style. The Studebaker Rockne doorknob faceplates support this idea.

So what does that suggest about the layout of the rooms?

First, there are four bedrooms in the house–the master, a second clearly set as a guest room, a tiny bedroom on the second floor with those rooms, and a room on the first floor near the original powder room and kitchen. I will take them in turn.

The master bedroom is quite large and would have been a luxurious space for these relatively elderly homeowners. It has features such as casement windows, two (large) closets and plenty of space for furniture. My guess is this was a big boost for Glenn and Agda in their 50s.

The guest bedroom would be considered a good-sized master bedroom and closet. And that leaves the third bedroom on the second floor: a tiny space. The owner previous to us used it as a baby’s room, and possibly other owners in the past had done so as well. For Agda? My guess is that this room was a sewing room for her. It’s a good size for that and it would have been a luxury not to have it in the basement. But perhaps not. Ideas welcome!

The first-floor bedroom has a very narrow closet, which makes it less than ideal as a bedroom. It has a common door to the dining room and another into the mudroom hallway that connects the kitchen, mudroom, and powder room. At one point, I thought I might have been a maid’s room, but then I learned through census data that the Welches never had (at least live-in) maids or housekeepers. It’s possible that they had workers who came in during the day.

Which also brings me back to the mystery extra back door. If they had daily workers–and they would have had them–used the second back door, that suggests that the first-floor bedroom was a “morning room” for Agda. The windows of this room face east, so is flooded with light in the morning, and is a comfortable size for planning the day, with easy access to the kitchen (and kitchen help) and a powder room. The small closet would be the perfect place to store essentials for the day.

At least for the past few owners, this space has worked as a home office. The clear yellow paint remnants on the wood trim (UGH) suggests others may have used it as something like a breakfast room.

We can only guess what Glenn and Agda cared about in building their home. But I think about it a lot in trying to honor the history and still make it our own.

I also am in awe that they got their permit to build their house at the end of July of 1936 and they moved in in January of 1937. That six months is about half of what it will take for us to rebuild the house to modern functionality and to our style.

Leave a comment