While a new world war looms

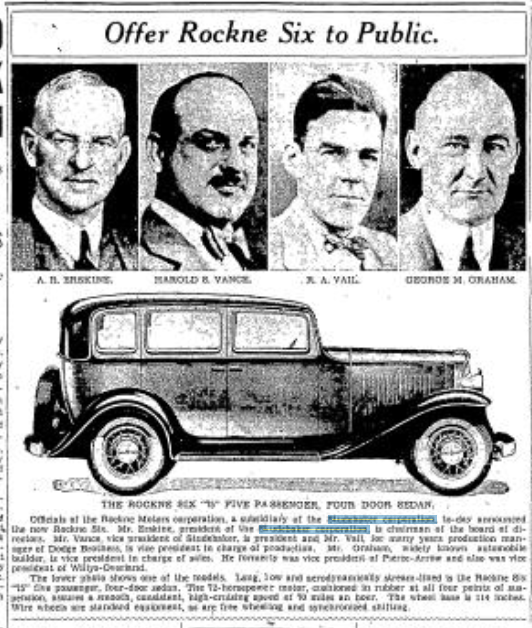

We don’t know the motivations of Glenn and Agda Welch for moving from their not-terribly old house on the west side of town to a new house in Coquillard Woods. We know that changing demographics in the late 1920s and early 1930s may have been a motivation. But the early 1930s, of course, was a time of great economic uncertainty, particularly where Glenn was an executive: Studebaker. The president of Studebaker at the time was Albert Russel Erskine. The South Bend Tribune refers to the downturn that we now call The Great Depression as a “general depression” throughout the early 1930s, while reporting on Erskine’s repeated rosy—to the point of farce—projections for the company’s future. Erskine was not reporting accurately. In fact, the company was increasingly teetering on bankruptcy. Was Glenn a senior enough executive to know this? Perhaps as assistant director of Traffic (which we would now call logistics). At the time, however, newspaper reports focused on upbeat company news such as the launch of the Rockne car line intended to be a lower cost vehicle affordable during the “general depression.”

The Depression, of course, was a challenge for all corporate execs, but Erskine made a series of missteps according to analyses reported in the Tribune including paying shareholders major dividends and then trying to cover that major loss with a merger with White Motor Company. By mid 1933, the company was in receivership:

With the receivership, Erskine was out as president and reportedly despondent. He died by suicide in mid 1933, more than $350,000 (about $8 million in today’s dollars) in debt.

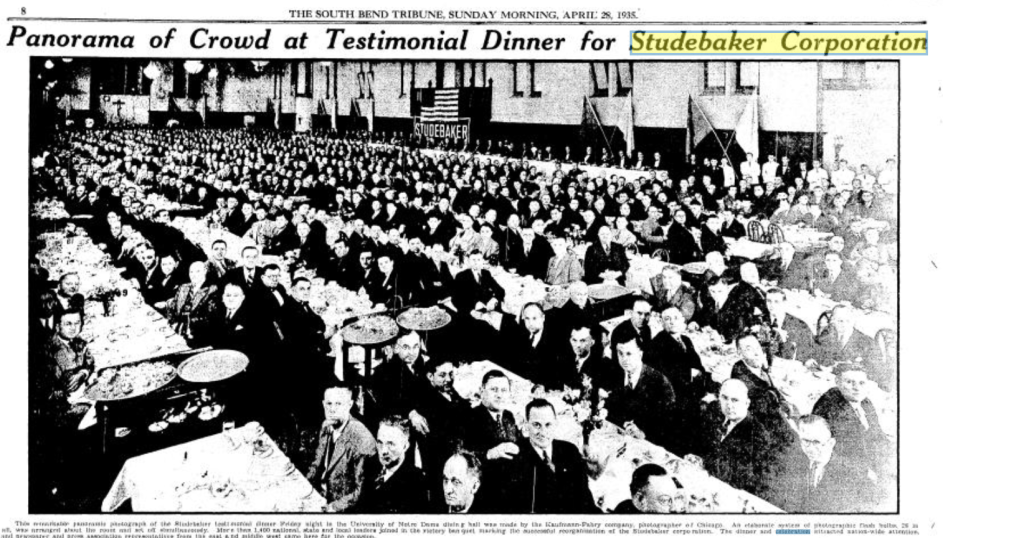

By the end of April, 1935, Studebaker emerged from receivership and South Bend had the largest celebration in its history, with an estimated 50,000 people celebrating in the streets and a major banquet with executives and political leaders—including Glenn Welch, whose picture is included in a display at the Studebaker Museum. (We know this because there is a similar likeness of him in an article from 1930 with photographs of executives.):

As we found this week, Glenn signed a building permit to build 349 N. Esther just a couple of months later. Perhaps Glenn and Agda had meant to build at the end of the 1920s, before the bust, and held off until Studebaker was in better shape. This would, of course, have been prudent. It also begs the question of his continued focus on the Rockne, which had been discontinued in 1933—a victim of the receivership.

Perhaps in South Bend—at least for Studebaker execs—the time seemed the end of turmoil. But take a look at the sub-head of the reporting on the end-of-receivership celebration:

Leave a comment