Bathrooms are just a practicality (and an expense at times) until they illustrate something about our culture: in our case deeply entrenched racism that impacts our residents to this very day.

As a simply practical matter, we have been consulting with plumbers to update a tiny bathroom in the basement. It only has fittings for a toilet and a tiny sink and, for some reason, some former owner poured concrete over the floor with some kind of cap over the toilet flange. We had assumed that this little bathroom had been added (and then covered over) by residents after Glenn and Agda Welch, the original owners. A neighbor who grew up in our house said that when she lived here (in the 1980s) they had planned to update the bathroom, but never had. A plumbing consultant today gave us new information that made me shudder: The plumbing fixtures are from 1936, when the home was built. This couples with other clues that I will detail later.

The Welches were a relatively wealthy couple in their 50s when they built and moved into the house. A few years after they moved in, U.S. Census reports that they had an income of $4,000, nearly four times the national median income at the time, and likely pretty nice for Indiana. That is the equivalent to about $87,000 today. Glenn Welch was an executive at the Studebaker company and newspaper stories of the time show that they entertained quite a bit. Why would an upper-middle class, fairly elderly (for the time) couple install a tiny powder room in the basement of the house–right next to the coal bin and furnace–that they would almost certainly never personally use? Although I have no documentation, it appears that it was likely because of racism and related redlining that was common in South Bend particularly when the Great Migration lured African Americans from the South to the North.

First, let’s step back a bit in Glenn and Agda’s life to give some context about the times. Glenn and Agda built (or at least bought) a new home in 1917 at 513 Blaine Ave., not far from his work at the Studebaker plant. It was a nice house on the west side of town and an easy walk to the plant. Here is what it looked like in good repair:

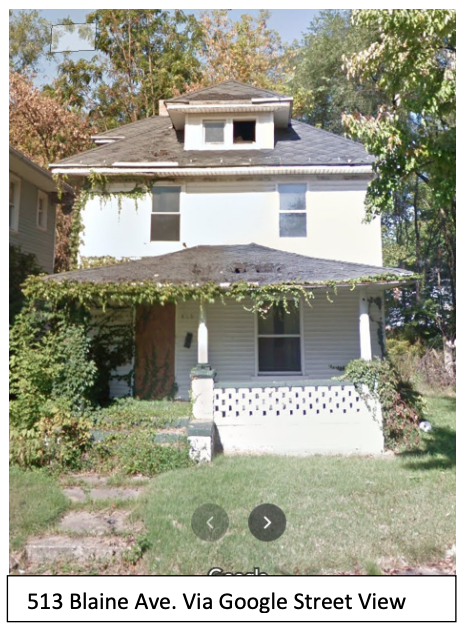

Folllowing is what it looked like in 2020 from Google Maps. It was demolished by the city in about 2021.

By 1933, after the Welches had lived there for 18 years raising their daughter, Gladys, their neighborhood had been redlined: declared yellow, or in decline, (https://s3.amazonaws.com/holc/tiles/IN/SouthBend/1937/holc-scan.jpg). Why? Largely because this part of town included a significant African American population often restricted to essentially slums near the plant. A recent Zoom session in South Bend with Realtors and important experts gives great context: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cO-nLj70I3I. One of the participants is historian at IU South Bend, Dr. Darryl Heller, where I studied and now teach. He explains in the video that a nearby neighborhood, Sunnymede, which was developed just a few years before Coquillard Woods, had formal, restrictive covenants that required sellers to restrict their rentals or sales exclusively to Caucasians. (Capital C).

At the time, Coquillard Woods was labeled “green” or “first grade”, which meant that white people could get a loan for a home, but others could not. Indeed, U.S. Census data shows in both 1930 and 1940 that the only residents were white unless they were “servants”, and those were consistently labeled as “negro”. Glenn and Agda never list anyone living with them, so they probably did not have live-in servants. However, as relatively wealthy people, they likely did have servants. This helps illuminate some of the oddities of the house.

One significant oddity is that we have two back doors that are reasonably close to each other. Why on earth would a relatively elderly couple want two back doors within feet of each other? One of them is closer to the garage–remember this is when the car is what made living here both feasible (not on public transportation to the factories) and common enough to have a garage. This garage has what looks like an original egress door not far from the first back door, which would have minimized getting snowed or rained upon. That door opens to a mud room that a homeowner would want to sit and ready themselves to go in or out. Right past the mudroom is a powder room and what I now think was Agda’s “morning room” that Dan uses for his office. It has a very small closet and is east facing, which is classic for a “morning room” in Agda’s prime years. It is likely that Agda spent her mornings there.

Another oddity was what I considered “dead space” of a tiny hallway closed off by five doors–five. One was the mysterious second back door. That, when closed, allowed one to open the door to the basement directly in front. To the right of entering the second back door, there are three doors: one to the kitchen, one to the living room, and one to a closet, which we and recent owners have used as a pantry. Here are some pics:

With the discovery of the tiny bathroom in the basement, I started to realize why this strange door and wildly enclosed 12×4 hall might exist: an entrance for African American servants to keep them separate from interaction (and demeaned) with the white homeowners. I have consulted with Dr. Heller and he suspects I am on target.

The owners required that people “not like them” go in through a separate entrance. I am horrified. And galvanized.

We want to update the tiny bathroom for practical purposes: to ensure that during our renovation with lots of workers (and us) have full toilet access. Now I am wondering if what we can do is at least start at illumination of the racism that not just hurt people at the time, but has continued inequity because of the inability of people to build wealth for their families through home ownership.

Glenn and Agda were rich enough to buy two parcels of land in 1936. Understand this: right after the Great Depression. After they built and moved into our house, they built a house next door to their own for their daughter and son-in-law. Gladys and her husband lived in the house at 513 Blaine Ave. until their new house was move-in ready.

Today, the house at 513 Blaine is demolished after falling into complete disrepair (and perhaps worse.) Gladys, her husband and children, moved to California months after Glenn’s death in 1958.

Coquillard Woods residents are still primarily white, although it is much more diverse. Every owner of our home has been white; redlining effects still exist.

As I learn about the inequities demonstrated by my beloved house, I am in deep thought about what I and we can do to mitigate the sins that we white people used to subjugate others. I am on a mission.

Addendum: my very bright stepson (a characteristic he shares with his sister) asked me an important question: Can we confirm this? The short answer is no without diaries of the owners, builders, or relevant others. Do historians have better ideas for us amateurs?

Leave a comment